In ‘My Hideous Progeny’: The Lady and the Monster, Mary Poovey analyzes Mary Shelley’s career as a writer and personal life behind her gothic masterpiece – Frankenstein. Poovey’s writing largely deals with the concept of egotism and imagination and how these affect Shelley’s works and characters. Poovey also argues that Shelley constantly faced the battle between the urge to create and the anxiety of meeting the “prevalent social expectations that a woman conforms to the conventional feminine model of propriety.” To support her argument, Poovey analyzes the differences between the first edition (1818) and the second edition (1831) of Frankenstein, not only to bring clarity to some stranger changes, but to understand Shelley’s career transition in those years.

Victor Frankenstein

Even though Shelley claimed that she didn’t want to change any portion of the story or introduce any new ideas or circumstances, she made significant changes to the main character – Victor Frankenstein. In both 1818 and 1838 editions, Victor Frankenstein appears as an egotistic and self-assertive protagonist who ruins his life and people around him, but Shelley changed the origin of Victor’s creative urge in later editions. Poovey describes that, in the 1818 edition, Victor is driven by his innate desire and imaginative activity and believes that “his desire to conquer death through science is fundamentally unselfish and that he can be his own guardian.” But for Shelley, desire must be regulated by domestic relationships because it can protect oneself from the external world. Shelly suggested “as long as domestic relationship govern one’s energy, desire will turn outward as love”. Victor abandons his home to pursue his desire in both editions, but domestic relationships present as an option for him in the 1818 edition.

In the 1838 revision, Shelley depicted Victor as the “helpless pawn of a predetermined ‘destiny’, of a fate that is given, not made”. Because Victor’s destiny is doomed, he is powerless and helpless to change his fate. He must leave his family to create the monster. Shelley wrote, “such a man has virtually no control over his destiny and that he is therefore to be pitied rather than condemned”.

The monster

In the monster’s narrative, Shelley indented to make the monster a symbol of the consequence of Frankenstein’s self-assertion. Animating the monster gives Victor Frankenstein’s imagination a physical form. It fulfills Victor’s innate desire, but eventually destroys his domestic relationship while the monster kills his family and friend. Poovey also argues that the monster seems simply the agent of Victor’s desire, but it also presents to be a “Godwinian critique of social injustice.” The monster’s story becomes “a symbolic extension of her comment on the ego’s monstrosity, an inside glimpse of the pathos of the human condition.”

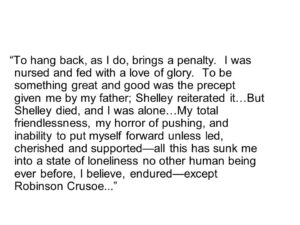

Poovey also makes the point that we cannot understand Mary Shelley as a writer without considering her as a person. Mary Shelley was the daughter of two prominent people, William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, then the wife of Percy Shelly. “Shelley was encouraged from her youth to fulfill the Romantic model of the artist, to prove herself by means of her pen and her imagination.” According to Poovey, Shelley constantly felt the pressure to be something great and as Shelley herself put it, she was “Nursed and fed with love of glory.” Shelley’s stepsister Claire Clairmont once wryly remarked, “in our family, if you cannot write an epic poem or novel, that by its originality knocks all other novels on the head, you are a despicable creature, not worth acknowledging.” Shelley faced not only the pressure to be “original” with her writing, but the pressure to meet societal expectation that a woman should be self-effacing and supportive to her family rather than to a career. Caught between these two models, Shelley developed a pervasive personal and artistic ambivalence toward feminine self-assertion.

The first edition of Frankenstein was published in 1818, when Shelley was just twenty. Even though people were praising the work’s power and stylistic vigor, they also criticized its inappropriate subject and lack of a moral, which was an essential during that time. One of the first reviewers commented “Our taste and our judgment alike revolt at this kind of writing, and the greater the ability with which it may be executed the worse it is—it inculcates no lesson of conduct, manners, or morality.” Some of the critics even assumed the author of Frankenstein to be a man who is no doubt a follower of Godwin.

Later, in the introduction of 1831, Shelley felt guilty about her “frightful” transgression and apologized for her adolescent audacity. The primary purpose of 1831 introduction was to explain and defend the audacity of what now seems blasphemy. Shelley claimed, “How I, then a young girl, came to think of, and to dilate upon, so very hideous an idea?” In the 1831 edition, Shelley wanted to assure her reader that she was no long the “defiant, self-assertive girl who, lacing proper humility, once dared to seek fame and to explore the intricacies of desire”. Shelley also claimed to be “very averse to bringing herself forward in print”. While Shelley continued to write, her work became less subversive and her characters became more meek, domestic, and feminine. She subjected her characters to pain and loneliness. This allowed her to achieve both social approval and her desire to prove herself worthy of her parents and Percy Shelley.

Discussion questions:

- What is the effect of a series of first person narratives in the book?

- Do you agree that there is a lack of moral in Frankenstein? If no, what is the moral of this book?

- At the end of the Volume two, the monster asks Frankenstein to create a woman creature for him. Does Frankenstein have the duty to do that?